Nobody needs to be reminded who Ray Scott was, though, like a prism held in the light, he cast beams of different colors in different directions depending on one’s perspective. Several of those points of view are present here in Montgomery’s Frazer Memorial Church. It wasn’t Ray’s church; Pintlala Baptist Church was until he died in his sleep on May 8. His family thought the small country church down the road a bit at Pintlala wouldn’t be large enough to hold everyone attending Ray’s celebration of life Oct. 4. They were right.

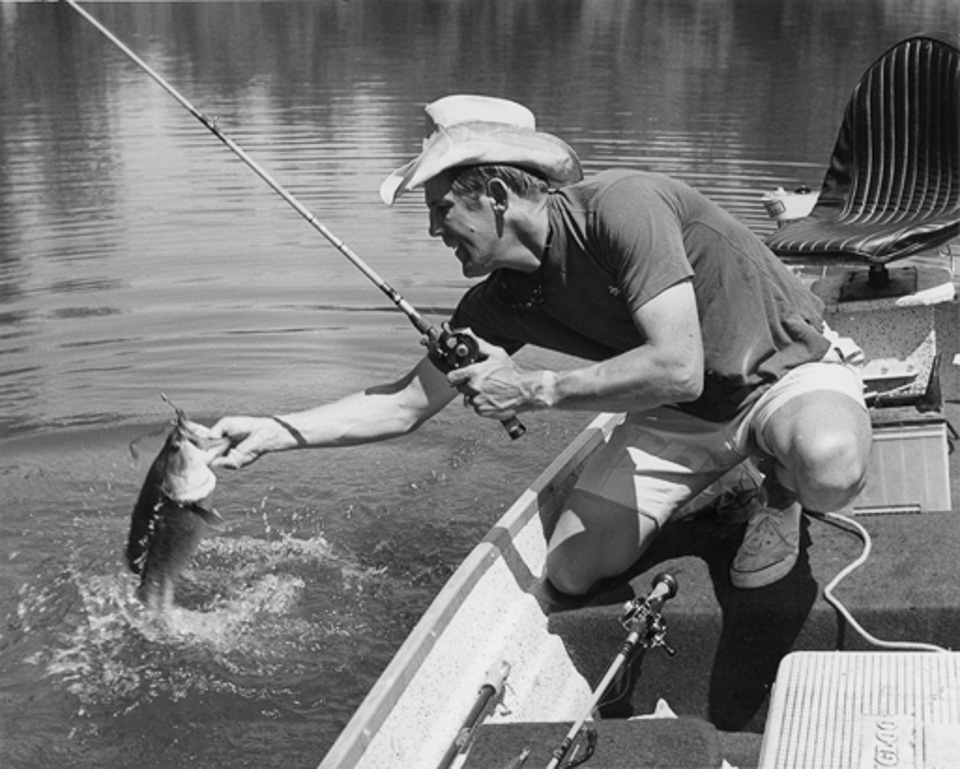

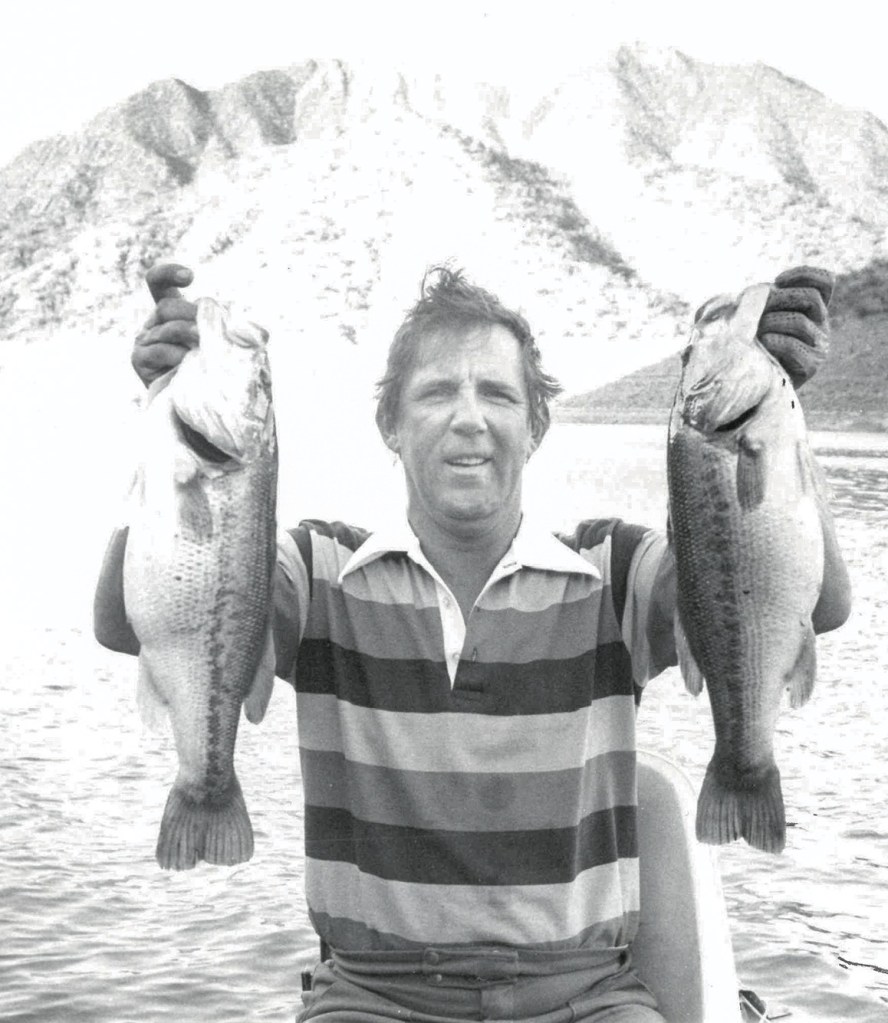

A celebration of life typically is a sort of recap of a person’s accomplishments. It’s a way to shed a temporary spotlight on dearly departed who otherwise might be, to some degree at least, anonymous. Not Ray; Ray’s send-off is more a reminder than a revelation, a summing up of the man who invented bass tournament fishing almost on a dare. In doing so, he created a sport whose ripple effect touched every corner of the fishing world, from boat and tackle company owners to the Joe Lunchbuckets whose aspirations for greatness were cheered on by the force of his charm and showmanship. In a real sense, Ray’s celebration of life is a reckoning from many perspectives.

It is also a collective recollection of an extraordinary personality who never met a mountain he didn’t think he could turn into a molehill, a circus barker who never shied away from the spotlights his sometimes-outlandish endeavors attracted. “What the mind can conceive, the will can achieve,” was his mantra.

Ray was known for unrehearsed comments that often caused his audience to react somehow and B.A.S.S. managers to cast furtive looks at one another. Ray was the sort of fellow who, whether it caused a ruckus or elicited laughter, made people shake their heads and say “that’s just Ray.” It wasn’t a handicap; it was a gift.

Years ago, at a B.A.S.S. tournament on the Ohio River, fishing was predictably bad and Ray asked the fishermen to bring anything in that would excite the crowd, even if it wasn’t eligible. Jack Westberry of Tampa brought in a fairly large catfish that drew oohs and aahs from the crowd when the fisherman held it up on the weigh-in stand. Ray made the most of the diversion. Ray asked Westberry what he was going to do with the unqualified fish.

“Throw it back, I guess,” said the fisherman. “Don’t do that,” said Ray. “Catfish are good eatin’. Tell you what; we’ll give it to the first fat woman who comes up here and claims it.” Some women in the audience frowned and fidgeted. Some men snickered and wiped grins off their faces. Nobody came forward. “Well, now we know there aren’t any fat women in Cincinnati,” Ray said finally. “You better throw it back.”

Most of the movers and shakers of bassdom are seated in the Montgomery church: Helen Sevier and Bob Cobb, Johnny Morris, Bill Dance, Roland Martin, Earl Bentz, Jimmy Houston and Hank Parker, among others. How could they not be there? Their presence is a show of respect and also an admission of Scott’s influence on their lives. Otherwise, if Ray Scott didn’t matter, then nobody did. He was the juncture where many paths upward bound met and went on. In ways that almost seemed fated by divine providence, he helped them gain the right roads, he provided the ways for them to realize their ambitions, he uncovered the roots of their individual successes in various enterprises. He was the source of legends that were mostly true. If he wasn’t quite spectacular, the results of his endeavors were.

In a sense, the grateful in the church share the pews with the ghosts of others who had played their roles and gone on: Forrest Wood, Don Butler, Harold Sharp, Stan Sloan, Jack Wingate, Ray Murski, Cotton Cordell, Jim Bagley and Tom Mann – ordinary men who achieved extraordinary fame and – more often than not – fortune.

There was a symbiotic relationship born in a time when nothing could be taken for granted, when everything was new and untested, which made it all the more exciting; Scott’s master plan needed dreamers and the dreamers of those early years needed someone like Ray to give their ambitions voice and purpose. To make it all work, B.A.S.S. had to appeal to the masses of rough-hewn fishermen who glommed on to the notion that their own stardom was a long shot, but a possibility nonetheless. Cue fanfare for the common man.

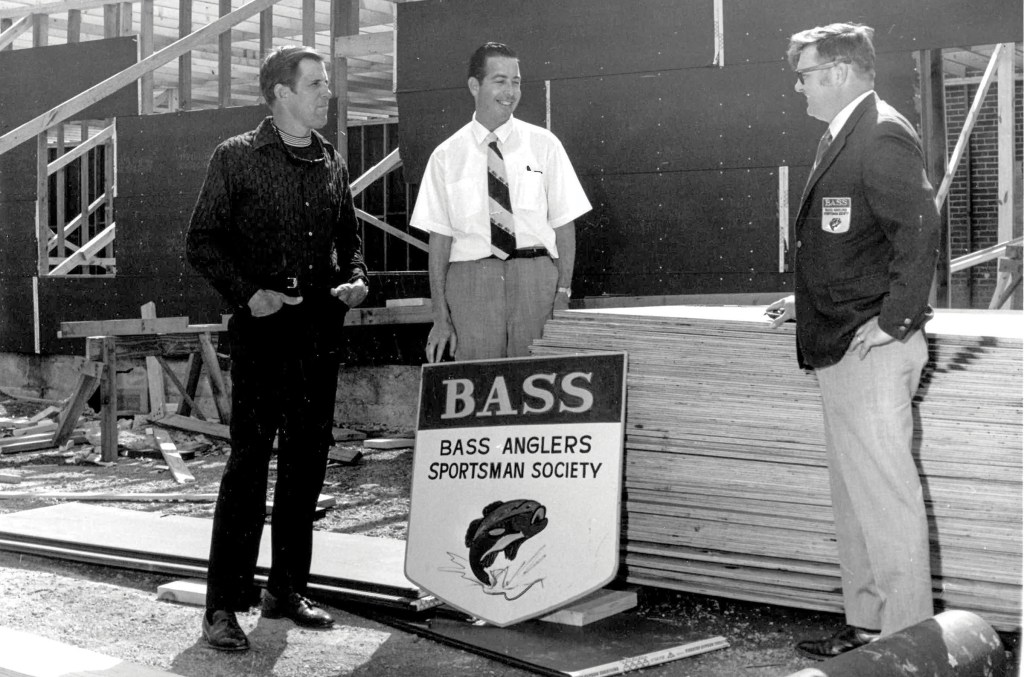

The birth of bass tournaments was part razzamatazz and part shell game rather than instant success. It required the guiding hand of a magician who could turn skeptics into true believers. Scott pulled it off, though not at first.

In its infancy in the late 1960s, B.A.S.S. was an idea that even he couldn’t live up to all the time, but he usually did. He liked people and he liked their spotlights pointed toward him. He didn’t hesitate to exploit his own celebrity and apply his considerable powers of persuasion to a cause that he was behind. All the zigzagged paths that emanated from the founding of B.A.S.S. led back to him in some form or fashion. He had a gift for turning a no into a yes, and he used it often in the formative years. Nothing was set in stone with him. He could provide more than one answer to the same question and make any sound convincing.

Scott counted among his friends two presidents – the Bushes – and had a gift for gab that seemed better suited for politics than fishing tournaments. When asked why he never ran for public office, however, he replied that he knew he would enjoy the running part, but hate the serving part. Bureaucracy and the rules that went with it didn’t seem suited to his free-wheeling style. His ways were pliable. His wealth was a byproduct, something he earned, a sign of achievement against the odds, especially to a man whose humble beginnings suggested the deck was stacked against him from the get-go. Not everything worked, but by his reckoning, if it didn’t work, maybe the next thing would. And there was always a next thing.

One morning while waiting on a dock at Dale Hollow Lake for his boat to be brought up, Ray saw a fisherman and his wife come idling up to refill their 6-gallon fuel tank. He greeted them and, as the woman stepped off the front deck, he pointed at her feet and said: “I bet I know where you got them shoes.”

“How do you know that; you don’t even know me or where I buy shoes or anything else?,” she replied with a question of her own.

“Bet you a dollar,” said Ray. The man at the controls, who instantly knew it was Ray talking, encouraged the woman to bet him. When she agreed, Ray said “You got those shoes on your feet.”

“That’s not fair,” retorted the woman. “That wasn’t how you meant it.”

“You’re right,” said Ray as he reached into his pocket. “I owe you a dollar.”

“Get him to autograph it,” said the man.

“What are you going to do with it?” asked Ray.

“Frame it and hang it up on the wall,” answered the angler.

“In that case,” said Ray, “I’ll just write you out a check for a dollar. You’ll have my autograph and I won’t be out anything but my name on a piece of paper.”

B.A.S.S., his crowning achievement, started out humbly enough. Its two-fold mission was to hold competitive bass tournaments in a wholesome family atmosphere and promote conservation of natural resources. To some extent, the conservation part of the equation also served a useful purpose by marshaling the anglers who weren’t the next Rick Clunn or Denny Brauer into important service to the cause. Even in the shadow of the tournament circuit, Scott raised and marshaled a committed good-ol’-boy army of B.A.S.S. Federation faithful whose badge of honor was an arm patch with a leaping bass.

To think that people could make a living fishing with rods and reels was a ludicrous idea, but many of them did and claimed their own special niches in the doing. The ripple effect of the words that came out of Scott’s mouth and the actions that he took resonated through the fishing world. He was the P.T. Barnum of bass fishing, the dreamer, the guy who believed his own schmaltz and, eventually, made others believe it as well.

B.A.S.S. made Ray famous, even among those far removed from the world of fishing. Whether he planned it that way or not, B.A.S.S. was the alpha and omega of his life. Toward the end, he had lost his hunger, or at least that part that drove him to focus his considerable energy on the company. After all, he sold B.A.S.S. in the mid-1980s to Helen Sevier and a group of investors. In a sense, B.A.S.S. was Scott’s life’s work until the next life’s work came along. The challenge to him was selling a concept with seemingly fragile merits and making it profitable. He succeeded in almost everything he tried.

Ray once invited several members of the Montgomery media and local dignitaries to a luncheon where he and representatives of Alabama Fish and Game spoke about deer nutrition and how growing bigger whitetail bucks would have a positive influence in the hunting world.

“I listened to Ray talk for 30 minutes before I figured out that it was another way for him to make money,” joked one of the attendees, who knew Ray well enough to know that Ray had a gift for solving problems or filling needs that consumers didn’t know they had in the first place.

At the meeting, Scott talked about a new company he was forming with his sons called the Whitetail Institute of America. It was among the very first that marketed various nutritional products for deer, and it became another hugely successful enterprise. Scott, an astute decoder of human nature, understood that the same audience that supported his bass tournaments also had other interests in the outdoors, most notably deer hunting.

From bass to bucks; it will all go on without Ray Scott. B.A.S.S. celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2017 and a substantial majority of the fishermen who participate in B.A.S.S. tournaments now weren’t born until after that first one on Beaver Lake in northwest Arkansas in 1967. Once the star, Scott became a parody of himself and his heyday, a relic of those rousing years. But, then, the past is always the problem for 88-year-old overachievers like Ray. His contemporaries remember what he meant to the fishing tackle industry and the lives of rank-and-file fishermen in bygone times, but there’s not many of them left. And the young are drawn more toward tomorrow than yesterday.

Ray’s last years were crowned with good works. After helping to ensure that conservation was a cornerstone of the tournament scene, he championed the passage of various state and federal laws that benefited fisheries. He raised more than $1,000,000 for his home church by staging celebrity-studded bass tournaments on his lake. Most of the money came not from entry fees, but from the sponsorship of major players in the fishing and boating world. The involvement of President H.W. Bush, a friend of Ray’s, helped prime the pump.

Throat-clearing and muffled coughs; words of praise and remembrance. Where, O death, is your victory? Where, O death, is your sting? Fact and fable, man and superman, Pop to his family and Mr. B.A.S.S to the rest, all temporarily met in the sarcophagus of an Alabama church.

The celebration of life goes on. No matter how sincere, the speakers’ words seem not altogether adequate. Who was Ray Scott exactly? Not any one person, really. He was a character, a stargazer, a force of nature, unique; a man who thrived on challenges, a salesman par excellence, one who was just as comfortable among the mighty as the common people drawn by his personality. Finally, however the prism of his life glimmers, all one can say for sure is “that’s just Ray.”

The service ends and people begin to leave. Outside the church, somewhere in the oaks and pines that rim the expansive parking lot, a mockingbird loudly peddles its repertoire of calls to anyone who cares to listen. Scientists say that the mockingbird can mimic dozens of different birds. From time to time, amid all that cacophony of sounds, the mockingbird voices its own song.

And it is quite wonderful.

More Ray jokes/remarks

Ray was also fond of playing practical jokes or otherwise involving anglers in pranks. At one Classic weigh-in show in Montgomery, Ray had Paul Elias pitch boxes of cough drops out into the audience, claiming the bearded Mississippi pro was one of the original founders of Smith Brothers Cough Drops. Elias wound up winning the tournament (1982).

Orlando Wilson of Atlanta was among the contestants in the 1987 Bassmaster Classic at Louisville, Ky., and Ray decided to make the most of Wilson’s diminutive size. At a pre-tournament gala, Scott announced that, like The Masters golf tournament, the contestants in the Classic would all be presented with green blazers to commemorate their involvement.

When it came Wilson’s turn to don his jacket, it was obvious that the coat was several sizes too big for the Georgia angler, who was just a few inches over 5-feet tall. The coat extended to Wilson’s knees, and his hands were completely covered by the sleeves.

Wilson took the gag good-naturedly, but yelled out that he would get even with Scott. He never did.

Editor’s note: Colin Moore was employed at B.A.S.S. from 1986 to 2000. Among other duties with the company, he was the custom publishing editor, managing editor of B.A.S.S. Times and executive editor of Bassmaster Magazine. He left the company in 2000 to serve as executive editor of Outdoor Life magazine. In 2010 Moore became editor of FLW Bass Fishing magazine and served in that capacity until becoming editor emeritus in 2016. He now is a freelance writer and editor.