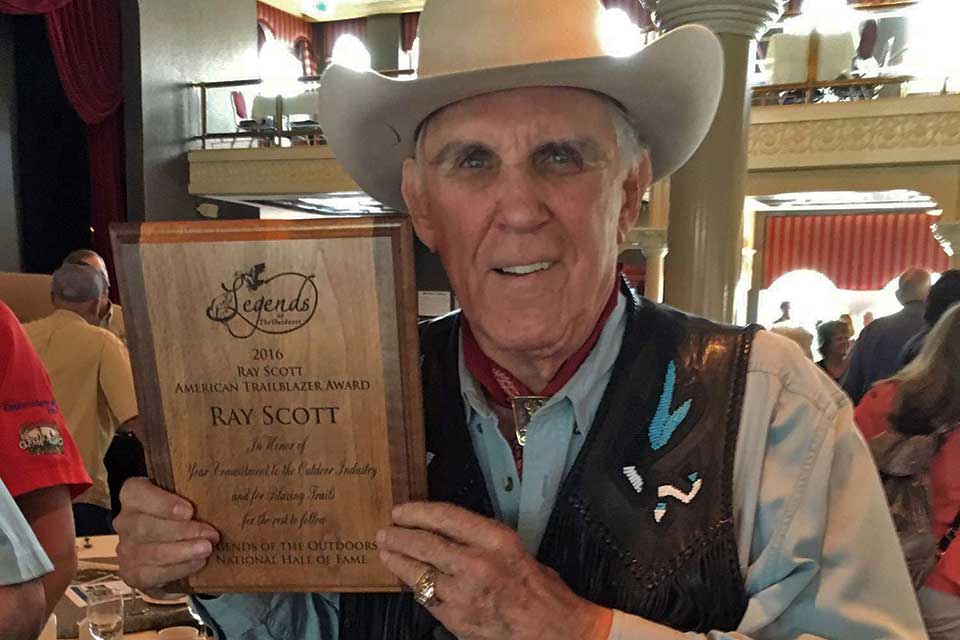

The merits of several bass fishing pioneers can be argued for inclusion on the sport’s Mount Rushmore, but Ray Scott’s place is carved in stone, a unanimous, first-ballot selection.

Similar accolades, along with mountain-size doses of love and respect, were abundant for the B.A.S.S. founder’s Celebration of Life Service on Oct. 4. Industry legends and dignitaries from far and wide were among those who attended the two-hour service at Frazer Methodist Church in Montgomery, Ala., with four speakers pinning their successes to Scott.

In their own ways, Bob Cobb, Johnny Morris, Roland Martin and Bill Dance eulogized Scott, who died May 8, 2022 at 88. They credited Scott with creating the mega-billion dollar industry that is bass fishing, offering personal tales of how they danced to the pied piper of B.A.S.S.

Among image and video presentations of Scott’s life and times, his adopted son, Wilson, offered a family perspective. Showmanship and learning to earn started early for Scott, who would amuse his uncles by standing on his head, as long as he got a nickel. Later, having his mother make extra sandwiches to sell to classmates lasted until a parent/teacher meeting.

There were numerous aspects of Scott’s life that Wilson lauded, and he even offered perspective on Scott’s second passion, whitetail deer. Scott was known to say he’d “make his bucks fishing and spent it hunting.” (See below for a previously published story on Scott’s first deer.) Wilson introduced a video exhibiting the gratitude Bassmaster anglers held for Scott.

“We all benefitted from Ray’s dream … he just drug all of us along,” said Billy Murray, who won Scott’s first Classis in 1971 then doubled up in 1978. “He’s the most profound single individual in our sport.”

“I don’t think anybody on this earth could have took it to where Ray has taken it,” Classic champ Larry Nixon said.

Cobb was Scott’s first hire and helped make his “Brainstorm in a Rainstorm” come to fruition. Cobb choked up several times during his presentation, first at repeating this line from a song, “We can make a dream together that will last forever.”

“Few men have discovered a new world or blazed a path across the country or built a new industry,” Cobb said. “Ray Scott achieved the improbable.”

Bass Pro Shops founder Johnny Morris, donning a jacket with a B.A.S.S. patch, said he whole-heartedly agreed with the memorial service’s title, The Dreamer.

“Ray helped dreams come true for many,” said Morris, who wondered what other pioneers in the business might have done if Scott didn’t first blaze the trial. “What a character. He was a kid who never grew up … the ultimate promoter for any sport.”

Morris, who also choked up, mentioned Scott’s influence now circles the globe, then recited his all-time favorite quote about fishing that pertains to Scott. “It’s not the big fish you catch, but the people you meet on the way.”

Martin has long given Scott credit for allowing him and everyone else the avenue to make a living in the sport. (For background, here’s the Daily Limit from B.A.S.S.’s 50th anniversary.) Scott had to plead with Martin to join his circuit, but once convinced, Martin was all in, becoming the second lifetime member. Martin went barnstorming with Scott and others, growing membership of the fledging organization, and there he saw firsthand how Scott’s prolific mind churned out tons of ideas.

“Ray Scott provided me more insight and inspiration than anybody,” Martin said. “It was a privilege to me to be a sounding board and listen to his ideas and how they developed.

“He was a predictor of the future … 50 years ago he was talking about today’s world.”

Dance was the final legend to address the mourners, and he echoed Morris, relating a call with him the day after Scott died. “He said thank God we were so lucky to get to know him and how blessed we are for the doors he opened.”

Scott’s widow, Susan, put together the event, perhaps for enhanced remembrance of her husband. Dance thought the need somewhat preposterous, because, he opened to laughs, “How in the world could you forget Ray?”

Very few change a game, let alone invent one, and Ray’s ripple became a tsunami, said Dance, who claims to have made the first catch in Scott’s inaugural 1967 tournament. Dance said Scott’s contributions can never be repaid, and everyone should keep his memory alive by continuing to utter his name.

“No doubt, Ray was a dreamer,” Dance said. “He was a promoter, a showman, a leader, a salesman, a marketer, a publisher, a conservationist, he was a motivator. Most of all, he was a father, a grandfather, a great husband to you, Susan, and a dear friend.

“How about it Ray, you catch one for me on the other side.”

Rev. Gary Burton of Pintlala Baptist Church, where Scott attended, joked he only had four pages of sermon before sharing his close bond to Scott. He shared Scott’s dedication to build his community, saying that many fail at the simple goal we should all strive to accomplish — leaving the world a better place.

Burton closed the celebration with the Fisherman’s Prayer, dedicated to its author, Uncle Homer Circle, and Ray Scott.

God grant that I may fish

until my dying day;

And when at last I come to rest,

I’ll then most humbly pray;

When in His landing net

I lie in final sleep;

That in His mercy I’ll be judged

as good enough to keep!

To keep Ray Scott in the minds of future generations, B.A.S.S. announced soon after his death that the Bassmaster Classic trophy will be named in his honor.

Daily Limit’s encounters with Ray Scott

The author first met and interviewed Scott at Garry Mason’s Legends of the Outdoors banquet. Jerry McKinnis, Don Logan and Jim Copeland had just teamed up to buy B.A.S.S., and Scott was asked for his take.

“ESPN has done a great job, except it’s a square peg in a round hole, and I say that with all due respect. They’re television. They’re not as spiritually involved,” Scott said. “Now, we got three men. First of all, all three know what a bass is. Number two, they all know how to catch one. And number three, they support catch and release, so that means I can come behind them and catch some.

“They are good men extremely capable in their specialty, namely in television with Jerry McKinnis, and then the other two, of course finance and publishing. You got a trifecta — I don’t how you could do better. I think B.A.S.S. has got its best days ahead.”

Scott got into more details, and vowed that his push to promote B.A.S.S. would continue. Ever the promoter/salesman, he noticed I wasn’t wearing a B.A.S.S. patch and set out to sell.

“I’m gonna make you a member of B.A.S.S.,” Scott said, handing over a form. “You just send that in.”

Are you kidding? He had membership forms in his coat pocket?

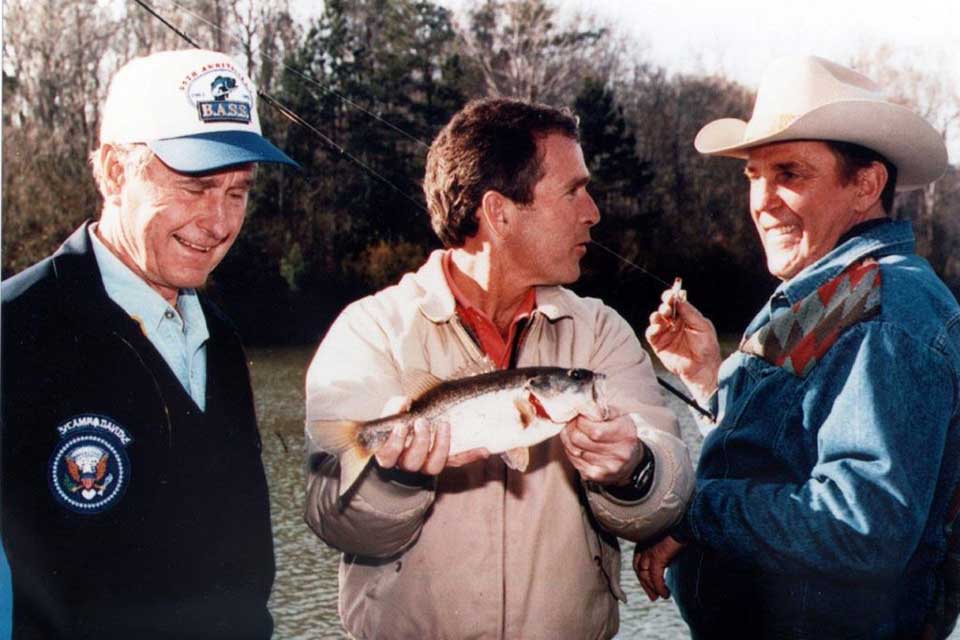

Fast forward to 2018. President George H.W. Bush died, and the phone number of Scott was forwarded in hopes of getting a comment about his friend. It was said Jim Keintz, executive director of Ray Scott Outdoors, could possibly relay a question to Scott.

Surprise. Scott picked up and gave a hearty interview about a “great man.” The next Scott quote ranks among the Daily Limit’s favorites: “I could call him in the middle of a war and he’d call me back.”

Here’s the story link in what might have been Scott’s last interview.

Godspeed, Ray Scott.

(Following was the story of Ray Scott’s first deer for a series, First in the Field)

Scott just as comfortable in deer stand as bass boat

Though Ray Scott’s name will be forever associated with bass fishing, he’s just as at home in a deer stand as he is in a boat.

His fondness for deer hunting was the catalyst that led him to form the Whitetail Institute in 1988 and to begin sales of Imperial Whitetail Clover, the first seed blend developed expressly for deer food plots and marketed nationwide.

Scott has hunted throughout the United States, Canada and Mexico, but it was an “old, scrawny Alabama buck” that he took in 1979 that ignited his love for deer hunting. Like most baby-boomer Southerners, Scott didn’t grow up in an era when deer and wild turkeys were abundant, or even available to hunters.

“When I was a kid, if you wanted to kill a buck in Alabama,” said Scott, who was born and reared in Montgomery, “you had to go to the area north of Mobile and along the Tombigbee River and put out some dogs.

“The credit for really getting deer back in Alabama goes to Charles Kelley, who was the head of the Game and Fish Division for many years. He’d have his people bring in whitetails from all over the country, and they’d stock a few here and there. Within a few years deer had multiplied to the tens of thousands. The state is covered up with deer now.”

When Alabama deer hunting was starting to become wildly popular in the 70s, Scott was preoccupied with building the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society. Consequently, he didn’t become an avid deer hunter until his company’s future was secured.

In 1979, however, Scott and Montgomery buddy John Nichols leased 300 acres of rolling hill country in Marengo County south of Demopolis and took up hunting in earnest.

“I didn’t know anything about deer except what they looked like, and didn’t have any idea about how to hunt them,” Scott said. “At the time, I owned a sporting goods business called The Outhouse, so I could grab any rifle I wanted and go hunting.

“That particular weekend in 1979, I was using a bolt-action .30-06. I don’t remember what make it was. One Saturday morning I just walked out to the edge of a clear-cut that was about 150 yards wide, sat against a tree and waited. The buck I shot came out on the opposite side and when he wasn’t looking my way, I raised the rifle to my shoulder, aimed and shot.?

The 4×2 whitetail “wasn’t much to look at,” as Scott remembered, but it weighed 190 pounds, which was heavy for an Alabama whitetail at the time. Nichols killed his first buck that same afternoon and, a week later, Scott’s son Steve, a high school freshman, downed his first buck.

“I was so full of anticipation, and I felt the same feeling every time I went hunting from then on,” Scott said. “There’s just something about that first buck. I don’t remember my second and third bucks, and so on, but I’ll never forget the first one. I don’t care how old you are when it happens, getting that first buck is like getting a tattoo on the soul — it just doesn’t go away.”