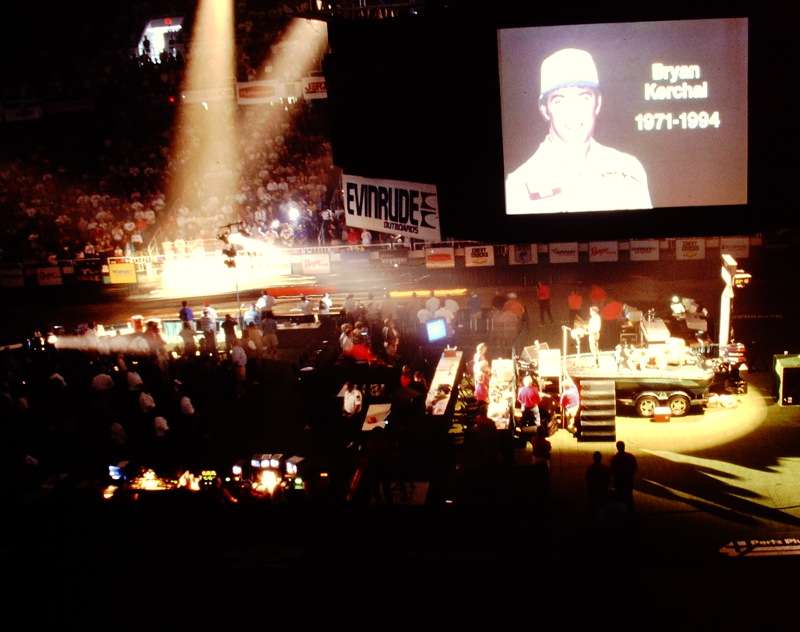

In complete blackness, a bass boat carrying only the spirit of a man was pulled through an arena, while thousands of people sat silent in the stands.

One year earlier, in July 1994, that boat carried a jubilant Bryan Kerchal, bearing an American flag and a brand-new Bassmaster Classic trophy, around the same arena. Seated in front of him, cheering, were his mother, his father and his girlfriend.

In July 1995, however, only the trophy sat atop the boat, which rode like a casket upon pall bearers’ shoulders. The parents and the girlfriend were in the stands. The only sounds were the engine of the truck and a military drum roll. That is, until the boat stopped, the spotlight that had shined upon the boat turned off, and the arena was filled with the sound of Kerchal blowing his fish whistle.

Like I had a hole in me

“It was one of the most poignant experiences I’ve ever had,” said Dave Precht, who was editor of Bassmaster Magazine at the time. “When that whistle blew,” … with a shake of the head, Precht’s voice trails off, as it does for most of the people who were in the arena at the time.

“I cried like a baby,” said Don Corkran, who was then the director of the B.A.S.S. Nation. “It was gut-wrenching. It brought all those emotions back.”

The scene was such a contrast from that of the 1994 boat ride — unrecognizable, really. The 1994 ride was the American dream, easy to capture all the joy of that moment in a single photograph. The 1995 ride was death.

For Chris Mann, a close friend and fishing partner of Kerchal, it was regret.

“I just wished I’d been there when he was in it,” said Mann. Twenty years later, Mann is ashamed that he didn’t go to Kerchal’s Classic. He was fishing another tournament when Kerchal won. But in 1995, he was there, watching an empty boat roll through.

“It was like I had a hole in me.”

Seat 3A

At 6:01 p.m. on Dec. 13, 1994, a last-minute weight disbursement change in the cabin of American Eagle flight 3379 would rock the bass fishing world. Although, no one knew it yet.

Bryan V. Kerchal, who had just won the 1994 Bassmaster Classic on July 30, was assigned to sit in 6B on the commuter flight. He was returning home from speaking at Wrangler’s Employee Appreciation Day, one of many sponsor engagements he had participated in over the past 4 1/2 months.

The agreeable Kerchal moved up to seat 3A, as requested.

Thirty-one minutes later, the plane broke apart in front of row 2. Kerchal was dead on impact.

The two passengers seated in row 6 survived.

Tell me anything, just tell me there hasn’t been a plane crash

Another hour and a half passed. Ray and Ronnie Kerchal got a phone call at their home in Connecticut. It was someone from the main B.A.S.S. Nation sponsor, Wrangler, where Kerchal had spoken earlier that day.

“He didn’t identify himself,” said Ray. “He only said he was from Wrangler and that he had put Bryan on that plane, the one that crashed, but that there were survivors.”

Ray and Ronnie turned on the news. The crash was the headline story.

Ronnie immediately knew Bryan was dead. Ray had hope. Their daughter, Deana, called every number she could find to get more information. For hours, the Kerchals lived in a very private hell, a blend of faith and despair, until they could learn more.

Meanwhile, Suzanne Dignon, Bryan’s girlfriend, was at LaGuardia airport waiting to pick him up. She was approached by two men in suits. Tell me anything, she said, just tell me there hasn’t been a plane crash. There has, they said.

It was six long hours before they knew for sure. Indeed, five people lived. Kerchal was not one of them. A spokesperson for American Eagle told them by phone at 2 a.m.

Before the sun rose, the pain was theirs alone. In those moments, Bryan Kerchal was not a Classic champion. He was not an inspiration to young people, he was not the hero of the B.A.S.S. Nation, and he was not even a fisherman. He was a son, a brother, a future husband, a best friend. He was, to the people who loved him most, unbelievably, just … gone.

It was not until the next morning that the word began to spread throughout the bass fishing world.

Like the world was ripped out from under me

Phones rang across the United States, the news spreading as quickly as it could in the pre-Internet era.

The reigning Bassmaster Classic champion had only come into the spotlight 4 1/2 months prior. He was an unknown, one of the five representatives of the B.A.S.S. Nation who had earned a spot in the Classic. But he had worked his way into the hearts of fans in that short period of time.

Friends called other friends with the news all morning long. At B.A.S.S. headquarters in Montgomery, Ala., the phones were ringing, too.

“It was tough,” said Don Corkran, then the director of the B.A.S.S. Nation. “It was like somebody hit you in the stomach.”

While Corkran was on the phone with Kerchal’s parents, working on creating a memorial fund to avoid what Corkran predicted would be “tractor-trailer loads of flowers showing up on the Kerchals’ doorstep,” others were still in shock.

“I just felt like the world was ripped out from under me,” said Sylvia Morris, a close friend of Kerchal’s who is now the president of the Connecticut B.A.S.S. Nation. “And the news had no idea what the Bassmaster Classic was. They kept talking about it like it was some sort of small race or something. The reporters had no idea what a huge thing Bryan had accomplished.”

Mike Iaconelli, 22 at the time and a member of the New Jersey B.A.S.S. Nation, heard about Kerchal’s death from a guy in his bass club.

“We all thought there must have been some mistake,” said Iaconelli. “We were just devastated, even though none of us knew him. We were emotionally committed to him, after what he had done. We didn’t even really believe it until we saw it on the front page of B.A.S.S. Times.”

For those who did know him, it was like time stood still.

“It was one of the longest days of my life,” said Ed Cowan, who was a member of the New York B.A.S.S. Nation and a friend of Kerchal’s.

“I just laid in bed looking at the ceiling, not even believing it after I heard it,” said Frank Giner, a fishing partner of Kerchal’s. “It didn’t seem real.”

Nothing seemed real

Nothing seemed real

Nothing seemed real. The wreckage was still smoldering in the forest in North Carolina when the Kerchals and Suzanne Dignon went to see it. They wanted something — anything — to take home with them.

“We took a pine cone and some sand,” said Ray Kerchal, Bryan’s father. It was the only concrete thing they could hold onto at the time. It felt like the only thing left of his 23-year-old son.

Paper fish

Within days, a memorial service materialized. Newtown, Connecticut, a picturesque, quiet little town — that nearly 18 years later to the day would host one of the nation’s greatest tragedies after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting — barely felt big enough to host all of the mourners.

The service attracted hundreds, many from other parts of the country. Don Corkran and Ray Scott traveled from Montgomery, Ala., to speak on behalf of B.A.S.S., Rick Clunn — the bass fishing legend from whom Kerchal had derived his inspiration years before — delivered a eulogy, and Karen Cole of Wrangler in North Carolina — who had taken Kerchal to the airport on that fateful day — gave a tribute as well. Some of Kerchal’s best friends and fishing partners spoke at the memorial or served as pall bearers. Paper fish dangled from the ceiling at the entrance for attendees to take.

“They told us to take a fish,” said Sylvia Morris, “because if Bryan was here, he’d rather us all just be out fishing.”

The memorial was so crowded that friends and family had to park several blocks away.

The announcement of his death and of the service was placed as a last-minute insert in the Connecticut B.A.S.S. Nation’s newsletter — one that, because of the publication’s timing, was actually reporting on his Classic victory.

The memorial was the first of many tributes to Kerchal. Another came in April 1995 at the B.A.S.S. Nation Championship, when an empty boat rode through the weigh-in in a much less dramatic but no less emotional nod to Kerchal than the empty boat that rode through the Classic arena that was to come that July. Memorial tournaments began being held in Kerchal’s name in Connecticut the year after he died, and those still continue, 20 years later.

The Bryan V. Kerchal Memorial Fund, which opened the day after the crash, supported the Bryan Kerchal Fishing Camp for its 10-year run, and has also funded other programs that give kids the chance to fish who wouldn’t otherwise have the opportunity.

“It’s what Bryan would have wanted his legacy to be,” said Ronnie. “He wanted everyone to experience fishing, and he wanted kids to believe in themselves and in their dreams. This is Bryan’s work; we’re just the facilitators.”