You've worked hard all week just to make it to Saturday, the one day you can forget about work and other obligations and enjoy a little time on the water. It's a glass calm morning, and as you zip up the lake, you anticipate getting to the honey hole that you're sure has never seen another angler. But as you round the corner, feeling the anticipation, your heart sinks as another fisherman approaches from the other direction.

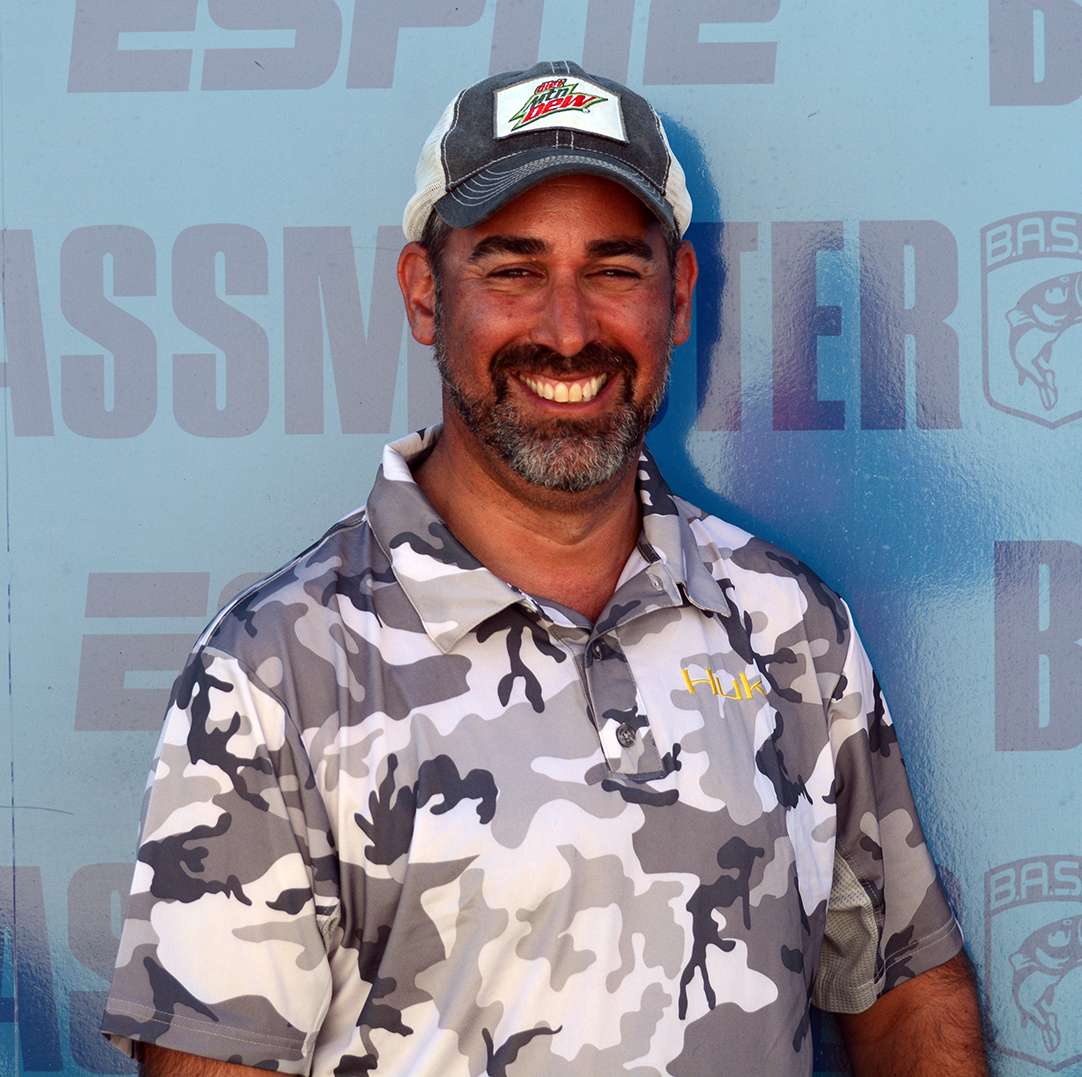

The feeling that our waters are shrinking at a rapid rate is common to Elite Series pros and weekend anglers alike. Improved electronics and mapping systems and an overall increase in the caliber of bass anglers means that nothing stays a secret very long anymore. "There's no way to avoid it because eventually you're going to be on the same fish as someone else," says 2007 Bassmaster Classic Champion Boyd Duckett. "We have no proximity rules in BASS. You can bump rubrails all day."

Duckett found himself in that position at the 2008 Bluegrass Brawl on Kentucky Lake. He ran 70 miles one way to his fish, only to find that veteran pro Gary Klein had his eyes on exactly the same area. They shared a large school of fish for three days. Duckett's first piece of advice on how to deal with this situation is to obey the golden rule. "We all want that secret hole to be ours, but it isn't.

Always be polite, always be kind," he says. "It'll get you further. Instead of trying to bully your way in or fight, you can talk to your opponent and work something out. If you're fishing a point, one of you work one side and one of you work the other. It's obvious you're both there, and you both have the right to be there. You're both on the bass or you wouldn't be there."

Once you've figured out a way to divvy up the area, it's important to fish your game and not let the other angler get inside your head. "The most important thing is don't think about it," Duckett says. "You have to just fish and forget about the fact that the other boat is there. At a lot of our events, anglers will be fishing literally side-by-side.

You've got to stay focused and feel like you're the only guy out there on the point — just you and the fish. You have no control of the other boat." If one angler is in contention to win and the other is out of the running altogether, the lower ranked pro sometimes relinquishes his claim on the hole, giving his competitor a chance to earn a victory. But if that's not the case, and you're committed to the area, you have to "get your mental groove and refuse to let it wreck your day," Duckett says.

He'll only leave if he thinks the area can no longer produce what he anticipated. "What I do there is no different than if I pulled up on a hump or a point or a ledge by myself," he says. "If I'm catching them, I'll stay. If I'm not catching them, I won't stay. The other boat should have no effect on your decision. You only stay if it's benefiting you.

Don't worry about what they're catching. It's the same decision you'd make if you were there by yourself. A lot of guys stay longer than they should. They want to catch those fish because the other guy is catching them, but you just have to blow through there and stay if you're catching them, or otherwise, move on." How did Duckett and Klein work it out at Kentucky Lake?

"He picked out his little area and I picked my area and we worked out some rules," Duckett remembers. "It was a tough deal but that didn't really bother me. I would have liked for him to have given me more room, and I'm sure he felt the same but we just fished." In an ending that could have been scripted in Hollywood, Duckett and Klein's willingness to work together allowed them both to finish in the money. Their division of the area was so equitable that at the end of three days of competition they had exactly the same weight.

"That's what you call 'splitting them,' " Duckett says.

(Provided by Z3 Media)