Fall is here. Temperatures are dropping. The first cold fronts slide through but don’t stick around long. It’s a great time to fish. No bugs. No jet-skiers. Your hunting buddies are in the woods so you may have the lake to yourself.

But the bite is off. What’s going on? A question we hear in the fall when fishing gets slow is “what is this thermocline everyone talks about, and what does it mean when the lake turns over?”

Here is a little limnology lesson. Let’s start last winter to see how we get to the fall turnover.

Water reaches its maximum density at 38˚F so the deepest water may be the warmest. Oxygen is plentiful and bass metabolism is slower so they don’t need to feed as often. Temperatures can be fairly uniform so they can live almost anywhere — but they will usually seek out the warmest water in their home range. Smallmouth will typically travel longer distances to find wintering areas than largemouth. Large schools of bass will often congregate in relatively small areas this time of year.

In the spring as the water gradually warms, fish get more active. Oxygen is good and their metabolism revs up. Feeding increases dramatically, and there is a general movement to shallower areas as the water warms and spawning instincts kick in.

As the season progresses and summer heat sets in, the water column becomes divided into three distinct zones because of different densities. The upper epilimnion is warm and oxygen rich. Because warmer water is less dense, it “floats” on the lower, colder water in the hypolimnion. This bottom layer is often devoid of oxygen. The narrow boundary layer between the warm epilimnion and the cold hypolimnion, where temperatures and oxygen levels drop rapidly, is the thermocline. You can often see this layer on your sonar because the layers return distinctly different sonar echoes.

In the summer, bass are confined to the warmer epilimnion where the temperatures and oxygen levels support life. Fish seldom venture through the thermocline into the oxygen-poor depths.

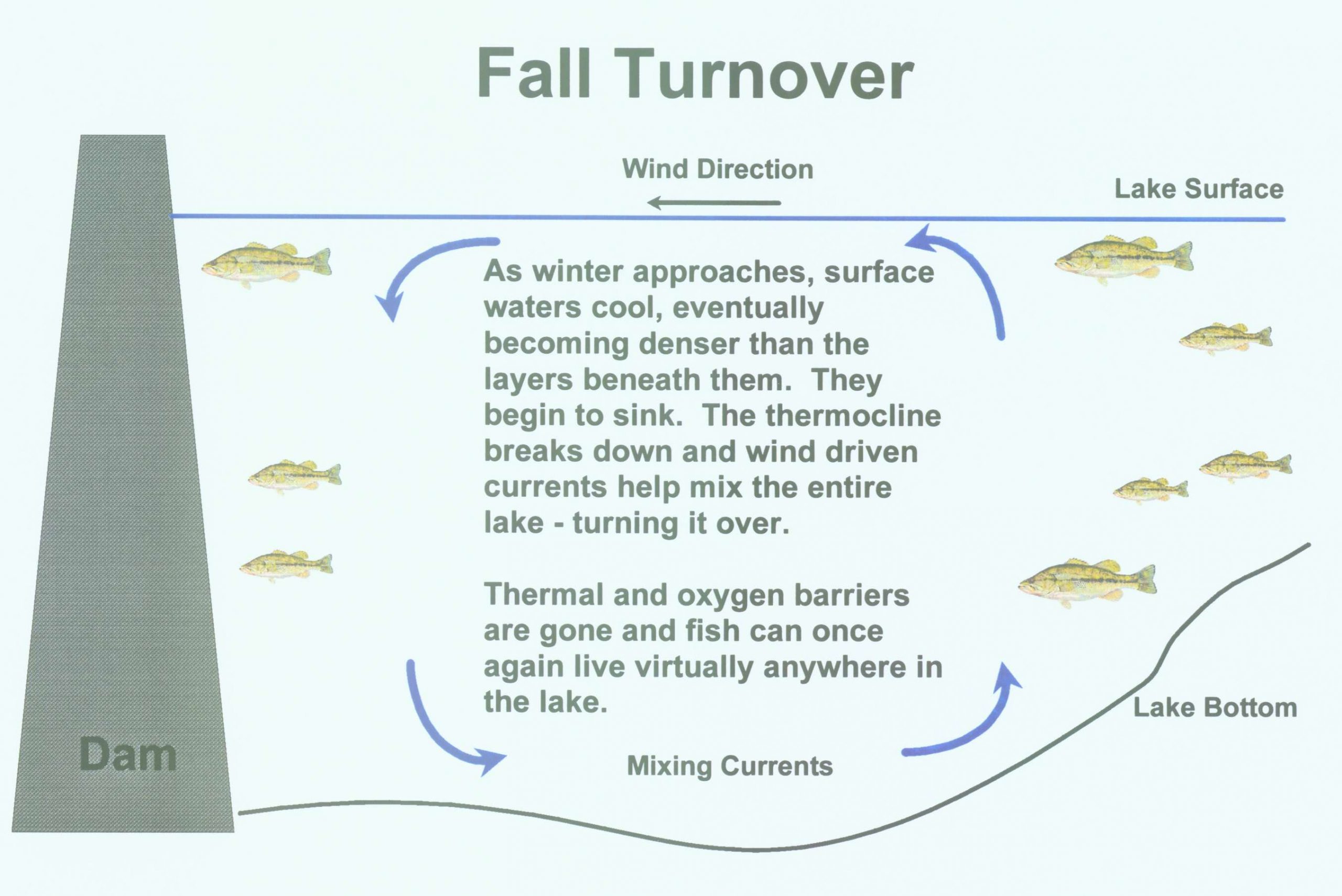

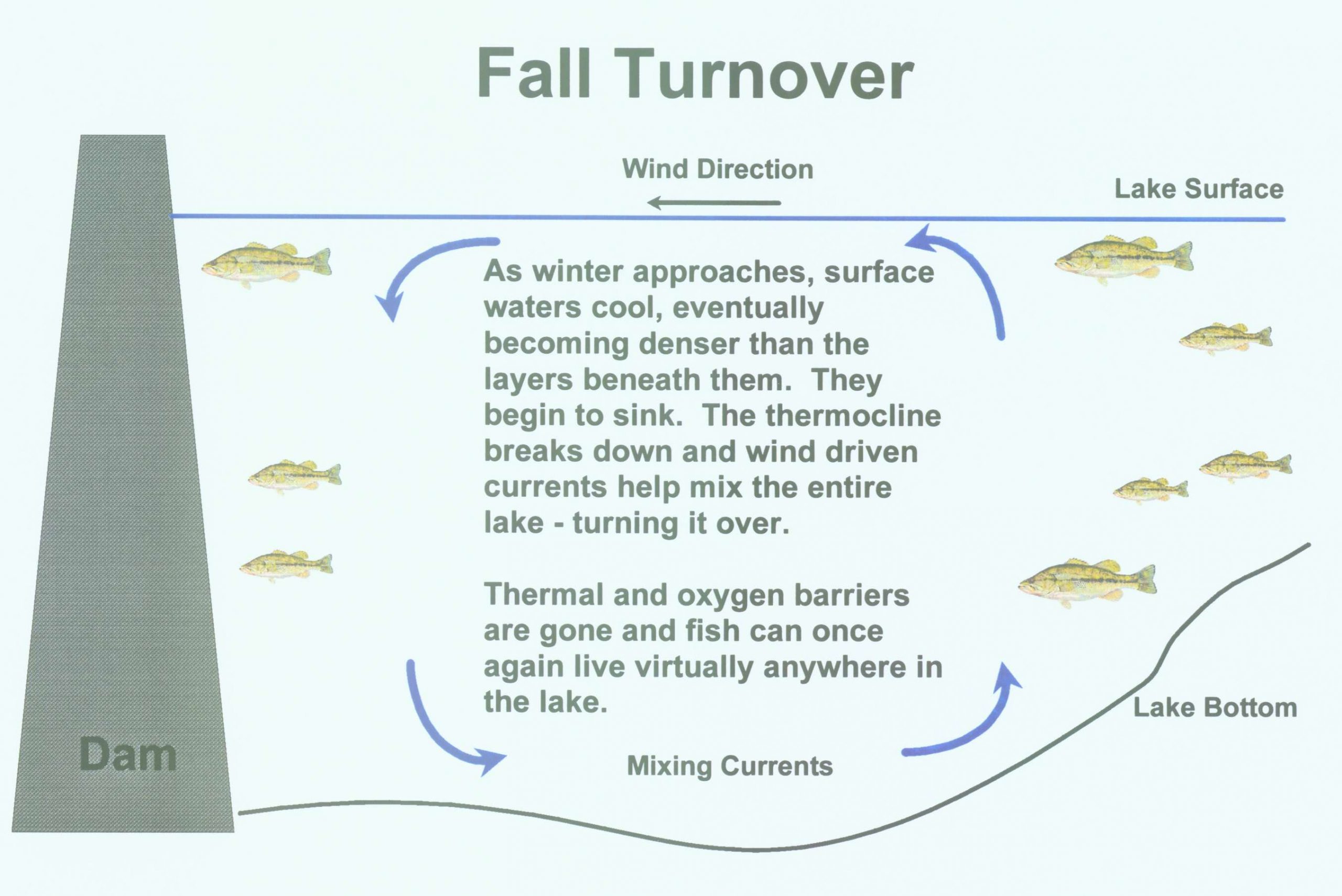

In the fall, the days get shorter than the nights and air temperatures begin to cool. Surface water temperatures drop and the water becomes denser. At some point, the temperatures (and density) are equal to the layers underneath. Winds create currents and push water from one side of the lake to the other. These currents hit the opposite shoreline and the now-denser upper layers are forced down, mixing them with the lower layers. This breaks the thermocline. As the surface waters sink, deeper layers are pushed up and the whole water column mixes. The lake literally turns over.

During this turnover there is a lot going on chemically too. As the bottom waters are forced up, they bring with them all sorts of organic material that has been sinking all year long. You often see this as lines what looks like grass clippings or debris on the surface. But because the water near the bottom had little oxygen, this muck has not been decomposing. Lakes often have a peculiar smell during turnover because decomposition produces sulfur compounds that stink.

As this organic-rich bottom water is pushed upwards it mixes with oxygen-rich water and very rapid decomposition can occur. This can use up oxygen to a point where it is stressful or even fatal to fish in confined areas. Most of the time however, the turnover does not kill fish, but it does stress them. They are disoriented and forced out of their summer routine.

Fishing often suffers too. After the turnover the fish are often harder to find. They are not squeezed into the upper epilimnion. They can live and feed anywhere. Temperature and oxygen content may be the same from top to bottom. Fish tend to scatter under these conditions.

As fall progresses, schools of baitfish often move up the creeks and feeder streams following plankton blooms that may continue for several weeks because the water is usually a bit warmer and nutrients may still be available. Forage fish simply follow their food supply. And while bass don’t swim long distances out of their home range, they will move off main lake areas into adjacent coves and creeks to follow their food.

Over a short period, these physical and chemical changes settle out and the bass get into more predictable patterns. As the water continues to cool and winter approaches, the system sets up to repeat this natural cycle.